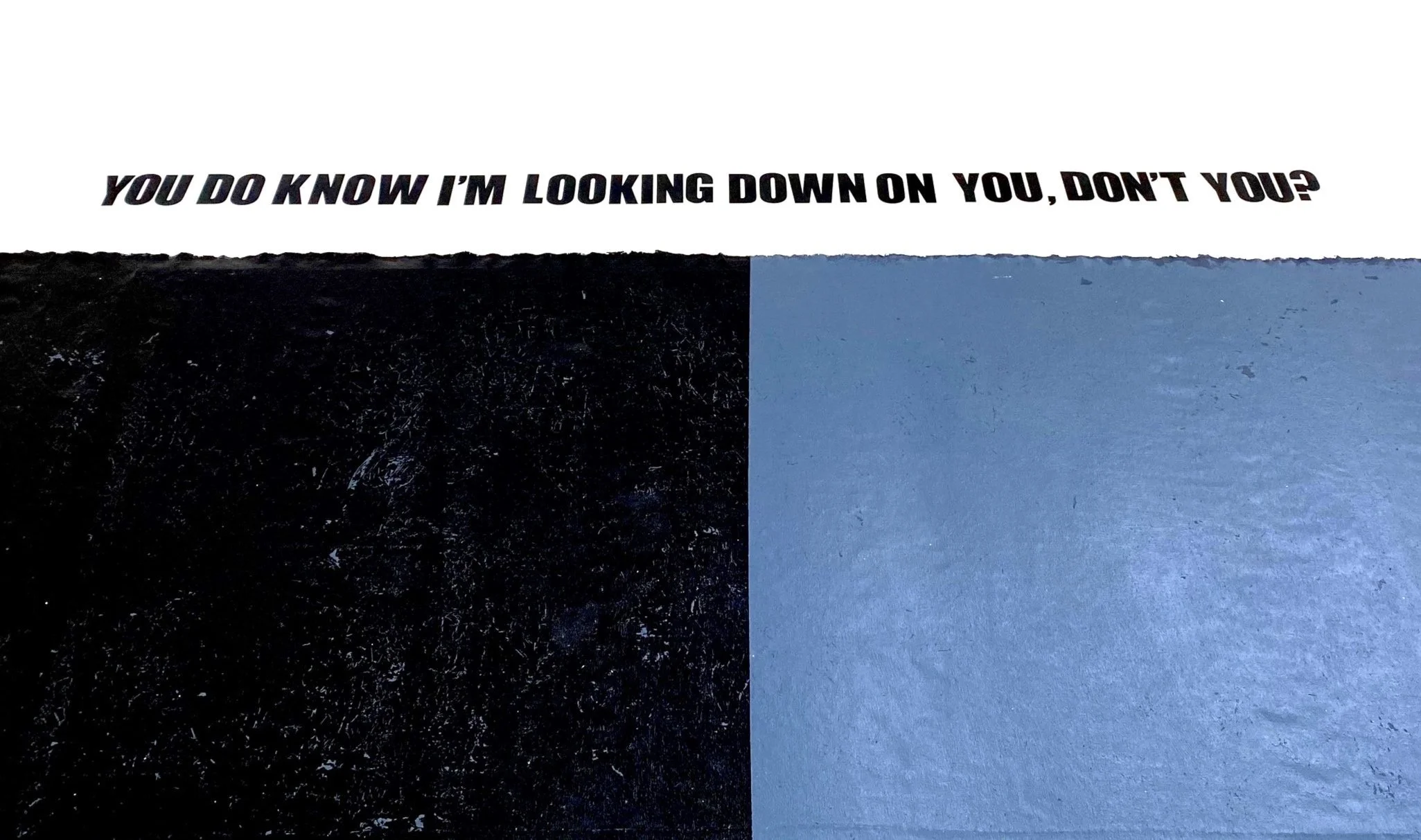

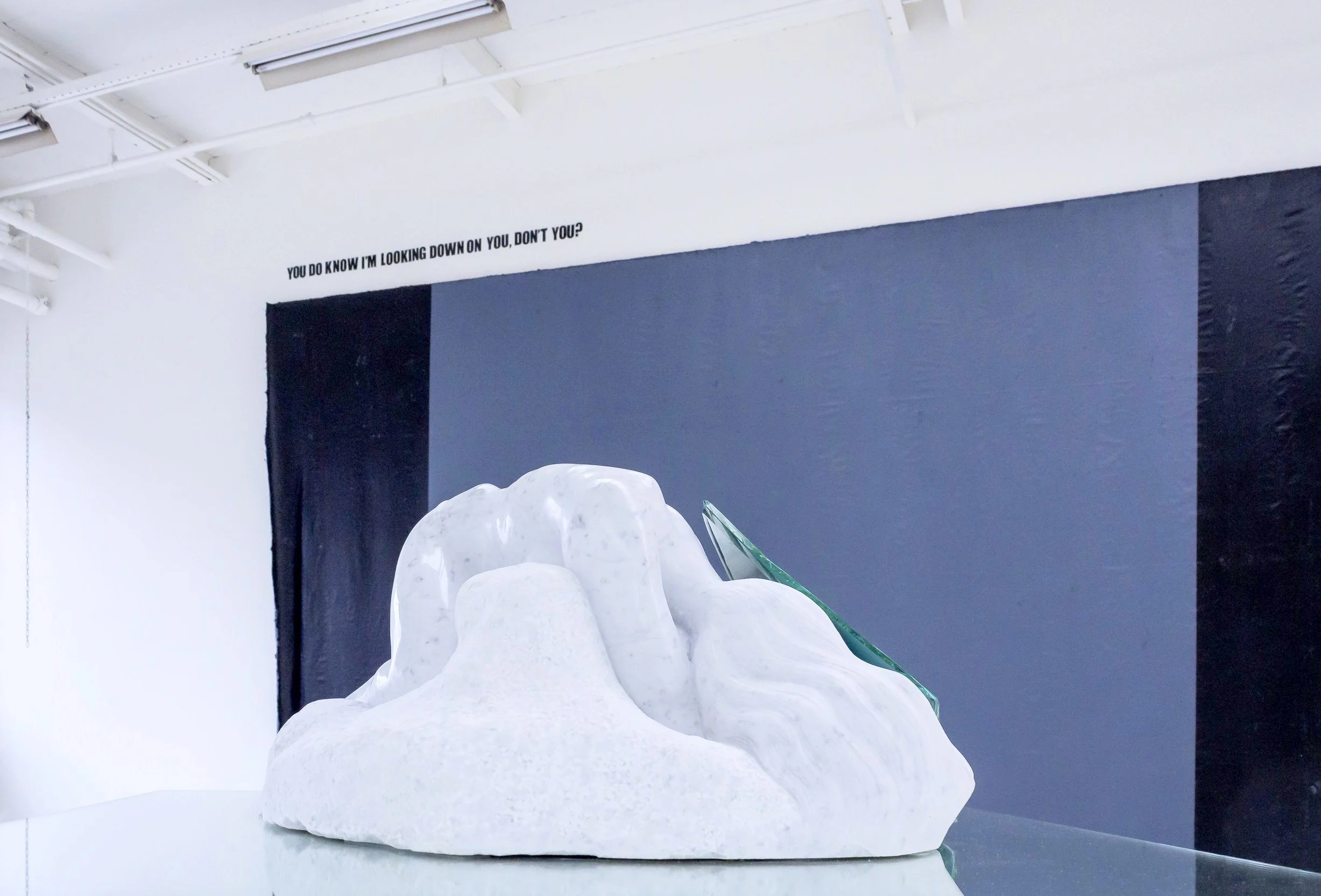

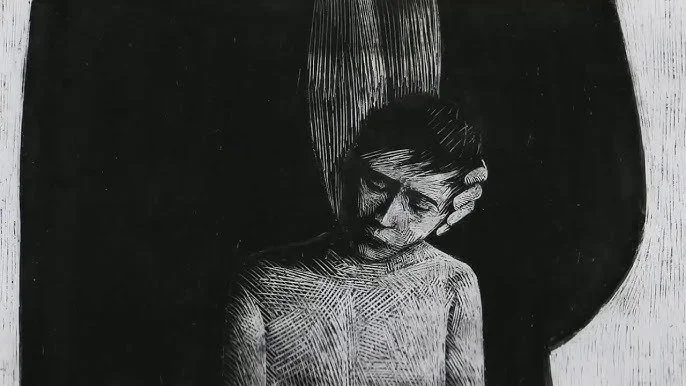

YOU DO KNOW I’M LOOKING DOWN ON YOU, DON’T YOU? is a piece about Conscience, (In)security, Omniscience, and Parent-Child-Dynamics.

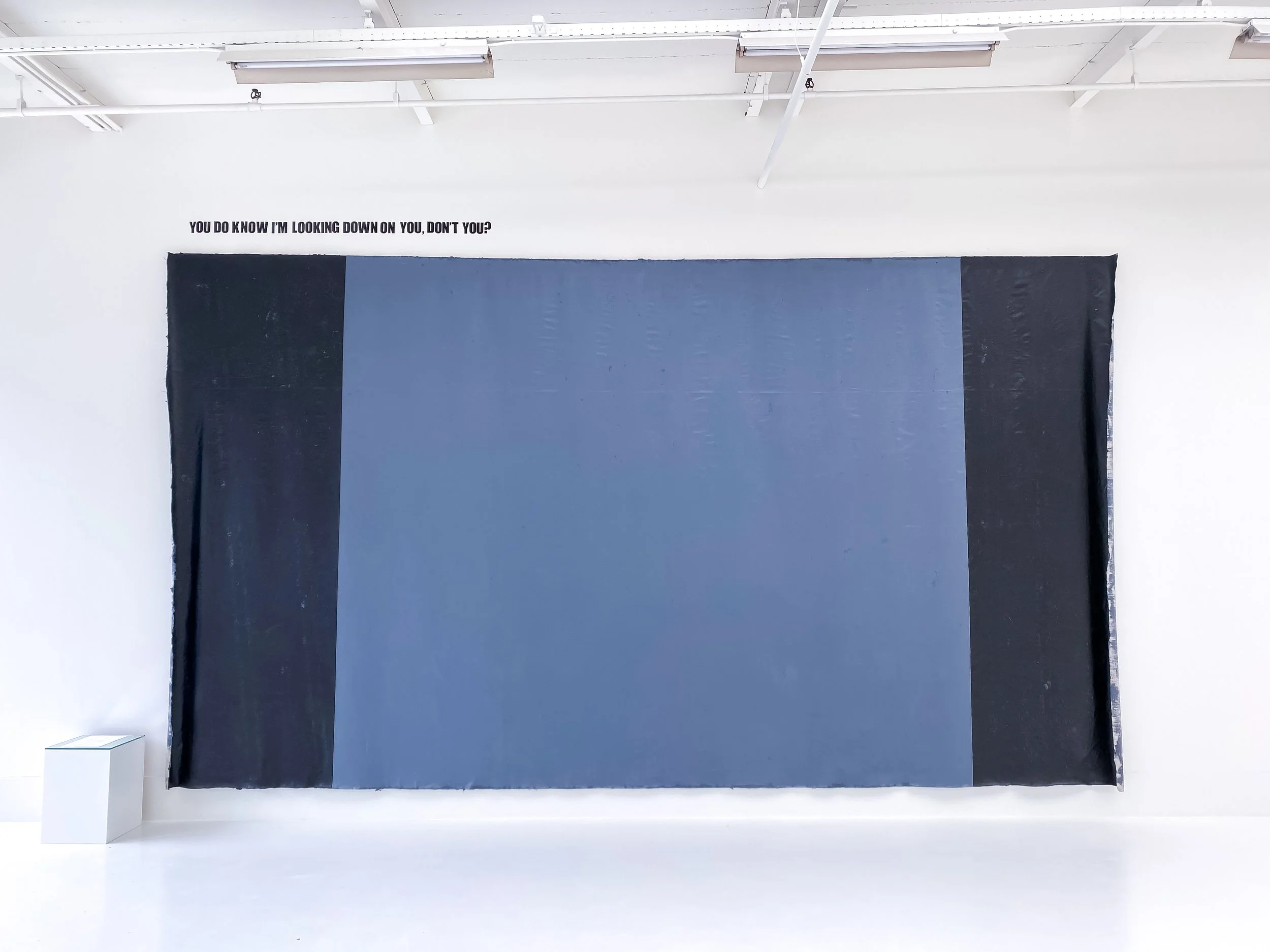

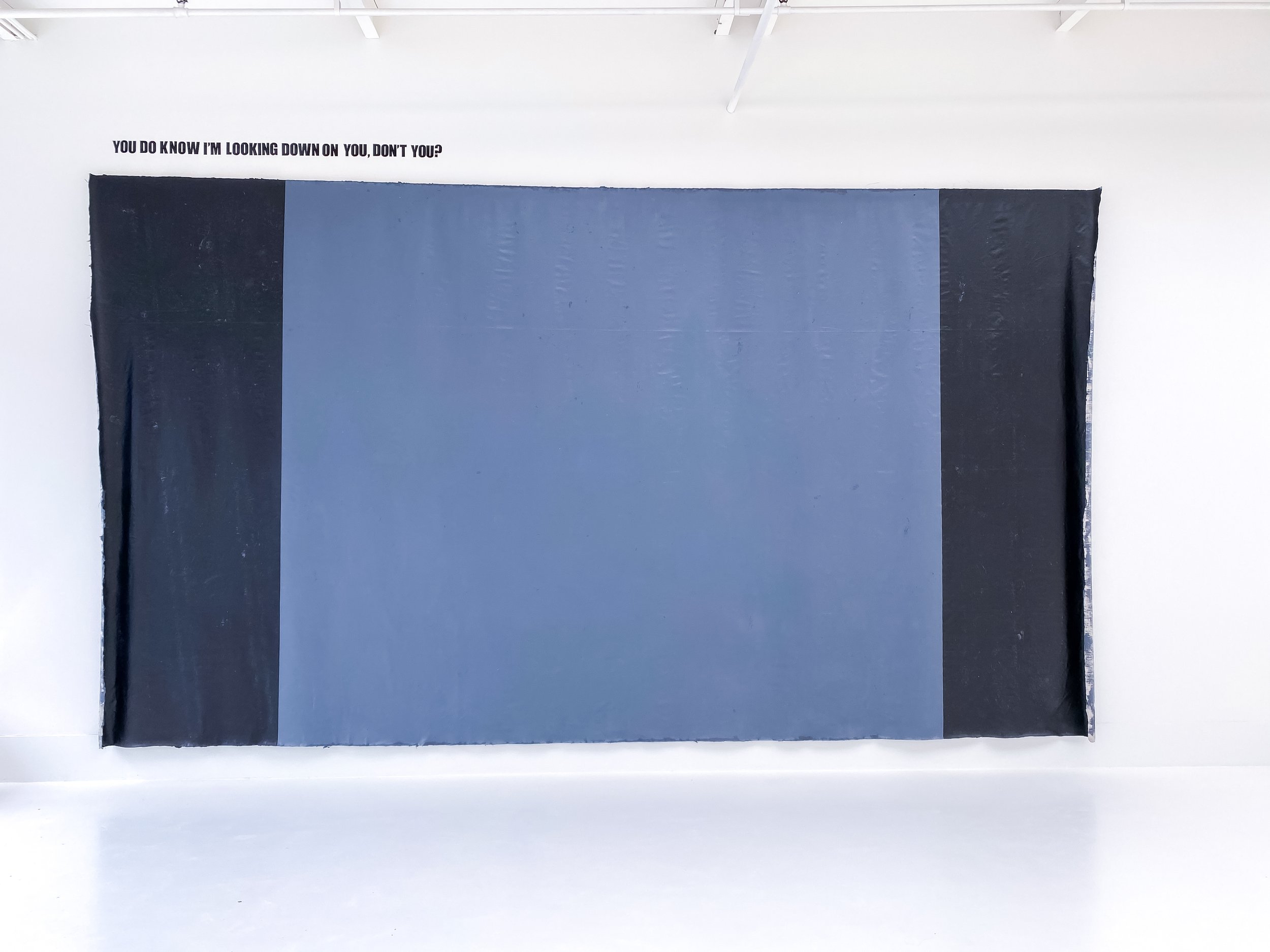

Acrylic paint on linen. Width 560 cm x height 316 cm x depth 10 cm, weight ca. 45 kg.

A massive abstract painting which goal is to overpower the spectator’s ego and uncover the unconsciously felt (in)security within the viewer.

YOU DO KNOW I’M LOOKING DOWN ON YOU, DON’T YOU? refers to various social and philosophical aspects and reflects on multiple psychological levels.

The art piece refers implicitly to several contemporary social-dynamic developments. The increase in people’s insecurity and self-doubt caused by social media and the innerly felt pressure to shine.

The distrust towards (big tech) companies and institutions, caused by the widespread power and manipulation through algorithms, (false) data, and secret intelligence; increasingly analysing and inluencing people’s actions and state of mind.

A big-brother-is-watching-and-manipulating-us-principle.

On a philosophical level, the words ‘YOU DO KNOW I'M LOOKING DOWN ON YOU, DON'T YOU?’ could be spoken by an Omnipotent-Omniscience, addressing the viewer directly.

The canvas is extremely large, still the text is placed above it, deliberately making the entity that pronounces these words larger than the art piece itself.

The omniscient speaker is situated above it all, and therefore does not fit into this physical framework. On the contrary the narrator of these words claims the infinite space above the canvas.

The art piece now, reaches out far from where it physically stops.

The art piece contains an efficacious self-reflective psychological functionality.

The spoken words reveal the spectator’s personally felt (in)security when one has the feeling of being addressed - belittled òr guided - by a certain person or persons in particular.

A young man for example associated the art piece with ‘dominant women looking down upon him giving him an unpleasant feeling of inferiority and female domination.’ While a woman in mourning indicated that she was ‘deeply touched’ for she felt that she was ‘being protected and addressed by her deceased partner.’

The words above the canvas could also be perceived as the voice of one’s conscience that gnaws and looks down on one’s actions and intentions.

Notice that the black areas on either side of the canvas are not same sized.

This deliberately applied imperfection will probably not be observed by the viewer, although the difference in width is considerable. This is the subliminal effect of a large-scale size.

The mind has already stuck the label ‘big’ on it. A further precise information processing mode of the spectator’s mind is therefore not being activated, while the brain automatically thinks of symmetry because this is most likely, since the bands are placed symmetrically on both sides. But in reality, this not the case.

Meanwhile, the use of dark colours - subliminal through association - emphasises the authority and menace of the assumed speaker of the words.

The black outer bands represent columns, that give the canvas and its fictional speaker above the canvas even more superiority and downsize, or possibly belittle, the spectator.

A principle used in temples and churches, to make the ego of man more void compared to a larger entity.

The canvas deliberately retained all signs of its original imperfections.

Symbolic for accepting the flaws of oneself as human being as well as embracing the imperfection and blemishes of life.

Without dualistic judgement, pursuant with the philosophical believe that no-one can be perfect, only the unborn and unformed, the divine is.

The purpose of the work is to make the viewer aware of one’s - suppressed - subconscious Self but not to give the spectator an unpleasant feeling per se.

The large-scale size of the canvas also works paradoxically liberating because the viewer’s ego gives in more quickly, and one can surrender to something larger - with more power - looking over you.

Like a child who feels a parent is in control of a situation and not the child itself. After acceptance it will create a certain safety.

Same aspects and psychological levels of the art piece, can be found in Pink Floyd’s song Mother.

The song, as much as the painting, wants the spectator to realise - how deep down we still feel small, full of doubt, anxious, and insecure, like a child. We tend to protect ourself and build an ego (wall) ‘Mother, should I build a wall?

But in addition to protection, the parent creates fear and unwanted - unconscious - cognitive patterns inside our heads. ‘Mother's going to put all of her fears into you.’

’The song ends with the words ‘Mother did it need to be so high?’

Is this our relentless need for recognition and urge to prove ourselves, or the demanding conscience that makes itself heard? Respond to one’s calling or not?

The inner voice that one might hear and dares to be submissive to. Or, if not, remains just like the conscience, a voice that you might choose to ignore…